T H E F I L M S T U D I E S W E B S I T E O F B E N T O N P A R K S C H O O L

David Walsh reviews a program of the filmmaker's works at the Detroit Film Theatre

25 October 1999

Born in 1932, Truffaut first came to prominence in the mid-

A number of Truffaut's works are permanent features of the film landscape of the 1950s and 1960s, including The Four Hundred Blows (1959), Shoot the Piano Player (1960) Jules and Jim (1962) and The Soft Skin (1964). I don't know that any of his later films had the impact those did, although Stolen Kisses (1968), The Wild Child (1970) Day for Night (1973), Small Change (1975) and The Last Metro (1980), among others, certainly found receptive audiences. Truffaut was only 52 years old when he died from a brain tumor in 1984.

As an artist he cuts an odd figure. Despite its many pleasurable and insightful moments, his body of work as a whole fails to leave a deep and lasting impression. One staunch defender (Don Allen in Finally Truffaut, 1994) perhaps says more than he wants to when he observes that “A common reaction to Truffaut's films is a sense of anticlimax.” Remarkably, another sympathetic critic (James Monaco in Cinema: A Critical Dictionary, 1980) expresses the same thought: “It was a critical commonplace in the 60s ... that both reviewers and audiences were always vaguely disappointed with a new Truffaut film.”

In fact, when one takes into account Truffaut's intelligence and sensitivity, his encyclopedic film knowledge (he claimed to have seen 4,000 films between 1940 and 1955, many of them repeatedly) as well as his grounding in literature, and his obvious skills as a director, his work does present itself to a considerable degree as a disappointment.

At their best Truffaut's films possess many positive qualities—lightness and informality, tenderness, sensuality, the personal touch. Positive, but perhaps not enough to sustain an artist in complex and difficult times. Particularly when they seem at least as much the result of a conscious plan to exclude certain human problems—specifically the problems of social organization—from consideration as they do the outpouring of a spontaneously lyrical personality. One almost always has the feeling that Truffaut has limited himself to the insubstantial as part of a larger artistic and intellectual scheme. Monaco admits as much, suggesting that we need to accept “Truffaut's intentionally limited spectrum of concerns.”

The films

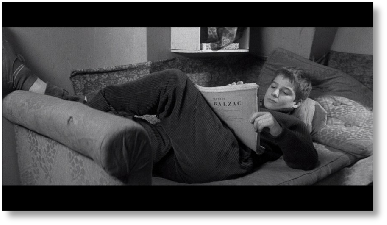

In The Four Hundred Blows, Truffaut's first and one of his finest works, he transformed aspects of his own unhappy childhood into fiction. In the film a Parisian youth, Antoine Doinel, tries to get by in the face of his parents' neglect or indifference. Petty crime leads him into trouble with the law and a stay in a detention center. He escapes, and the joyous moment when he rushes, arms open, toward the sea, savoring his freedom, is captured by Truffaut in a memorable freeze frame.

There are some lovely moments in this film. It has the flavor and pathos of life.

Here, in beautiful black-

There are troubling aspects, however, even to this film. For one thing, the director

can't entirely seem to make up his mind about its overall tone. More precisely, he

seems resolved not to imbue it with a tragic or semi-

Determinism is indispensable in art. Sustained unhappiness which is not shown to be necessary, rooted somehow in the structure of things, has a weakened impact because it fails to make a point of contact with the spectator's own, for the most part unconscious intuition that life is wretchedly and potentially tragically organized. Without provoking that convulsive mental state in which one thinks simultaneously, This had to happen! This shouldn't have happened!, there is no real tragedy.

Truffaut, for a variety of historical and ideological reasons, chose to reject this sort of determinism. As a result the tragic quality is all too frequently either absent in his work where the need for it is felt, as in certain moments in The Four Hundred Blows (and perhaps The Last Metro), or, more often, feels injected from the outside, arbitrary, histrionic (as in Jules and Jim, The Soft Skin and The Woman Next Door, among others).

There is another problem associated with The Four Hundred Blows that perhaps speaks as well to a larger issue. Truffaut was born as “the result of an unwanted and illegitimate pregnancy” ( François Truffaut, Diana Holmes and Robert Ingram, 1998) His mother, Janine de Montferrand, came from an aristocratic family; 21 months after her son's birth she married Roland Truffaut, an architect's assistant. (As a teenager François discovered that Roland was not his biological father.) The future film director spent his early years shuttling between grandmothers. When his maternal grandmother died in 1942, he came to live with Janine and Roland Truffaut in a small Paris apartment. His mother “scarcely tolerated him and his father was kind but weak and preoccupied.”

This is the period in his life fictionally worked over in The Four Hundred Blows, transposed to the late 1950s when Truffaut was actually shooting his film. In 1942 a more general unhappiness, of course, overshadowed the entire population of Paris. Northern France, including the capital city, was occupied by Hitler's forces. Resistance was met with arrest, torture and, frequently, execution. There were also considerable material shortages and economic hardships.

In retrospect I find it remarkable that Truffaut managed to set his story in the

1950s without making any apparent allowance for these facts. It does suggest a special

kind of blindness to have ignored the possibility that the conditions of German occupation—carrying

with them a continuous threat of repression and brutality—might have added to the

tension and psychic discomfort even in a petty-

Instead Truffaut preferred simply to point an accusing finger at his parents, especially

his mother, as the source of all his unhappiness. (He chose, in his fictionalized

version, to discount entirely as well the intense psychological and social pressures

someone like Janine, from a respectable Catholic family, must have come under in

1932 as an unwed mother.) One can find in this an unpleasant dose of self-

These two related tendencies—which manifest themselves as the inability to find the

right tone, or to integrate successfully conflicting influences and styles: French

“poetic realism,” Hitchcock, Italian Neo-

Read the great Roger Ebert’s review HERE

An analysis of camera movement in 400 Blows HERE

Crime and Punishment in Francois Truffaut's The 400 Blows

Critic Michael Klein stated in Film Comment that "The 400 Blows is a protest against

our concepts of crime and punishment." Throughout The Four Hundred Blows (1959),

Truffaut depicts protagonist Antoine Doinel (Jean-

The punishments he receives from his teacher result when he looks at a pin-

In the film, Antoine only commits one crime that is actually worthy of the term, the theft of a typewriter from his father's office. Yet, even that action seems little more than youthful folly. He steals the typewriter but does not realize that he will not be able to either sell or pawn it without a receipt because typewriters are numbered. Thus, he decides to return it to his father's office at the risk of being caught. This attempt seems to negate the severity of the crime and makes the resulting punishment—Antoine's exile to a home for juvenile delinquents—seem particularly harsh. Indeed, that institution and the various police facilities Antoine passes through on his way to the home are more repressive than either school or family. At the police station, he is moved from one cage to another and eventually into a cell. Literally caged, his spirit is also contained and confined while he is there. Then, he is sent to the home where even eating a few moments before it is time—a natural action for a growing boy—merits a slap.

Antoine eventually escapes from the home, but as many critics have pointed out, his escape does seem like a triumph over the system. Rather, he seems confused and forlorn. When he reaches the sea, it is not an accomplishment of a long time goal but a final disappointment or merely another boundary placed against him. Indeed, his experiences in the film have already denied Antoine of the freedom of childhood; his natural impulses have been repressed by unfeeling social institutions.

In his book, The Great Movies, William Bayer says "In The Four Hundred Blows society may have deprived Antoine Doinel of a portion of his soul" (218). Klein argues that Truffaut wishes to get us "to regard life with tolerance." Indeed, in the film, Truffaut presents tolerance for the little indiscretions and eccentricities that make us human is what allows the soul to remain intact and at liberty.

http://www.cod.edu/people/faculty/pruter/film/400bl ows.htm

Works Cited

Bayer, William. The Great Movies. New York: Ridge, 1973.

| Breathless |

| The 400 Blows |